Andra Jackson

Andra Jackson

November 1, 2008Jill Jolliffe knows that often in wars it is the heroes who are remembered while the suffering of ordinary people goes unnoted. But the Australian journalist, who has spent more than 25 years reporting on the East Timorese independence struggle, has found a way of ensuring that the memory of these silent sacrifices will be preserved.In 1983, Jolliffe landed an international scoop when a confidential Indonesian military manual made its way into her hands. It had been seized by Fretilin guerilla fighters during a raid on Indonesian military barracks, and smuggled out of East Timor.

It was a counter-insurgency manual with a section of advice on conduct to be followed when administering torture, to avoid later identification. It included admonishments such as: "Do not take pictures of people when they are naked, and make sure nobody sees you," she recounts.

Jolliffe, a longtime East Timor watcher, was working as a freelance journalist in Portugal, having been evacuated by the International Red Cross from East Timor in December 1975 shortly before Indonesia invaded in response to East Timor's declaration of independence from Portugal.

The manual was considered so significant that The Age, one of the newspapers Jolliffe was freelancing for, agreed to pay her to go to London and help Amnesty International translate the instructions from Indonesian Bahasa. It was assessed by an American Indonesian expert, after which Amnesty issued a statement condemning Indonesia's use of torture.

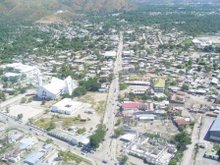

Now, 25 years later (and six years after East Timor finally became a sovereign state in 2002), Darwin-based Jolliffe is following up that story, working with the victims of Indonesian Government-sanctioned torture. She has established the Dili-based Living Memory Project, recording the experiences of East Timor's forgotten casualties of its long war of independence — its prisoners.

On return visits to East Timor in 1999 and 2001, she met many of the ex-prisoners whose names were so familiar from her own reports on their ordeals. Some had been imprisoned in the 1970s, others after the 1991 Santa Cruz massacre in which Indonesian troops opened fire on pro-independence demonstrators in a cemetery.

The idea for the Living Memory Project took shape as she chatted with them. "One of the problems is that these people suffer from a lack of recognition, if nothing else," says Jolliffe, who speaks in measured terms. "Many suffer from broken bones and long-standing medical problems but psychologically also, they have felt very excluded from the independence process, and not recognised. They are mostly civilians, held by the Indonesians. One-third of them were women, some with children."

While many of the former independence fighters have been accorded hero status, she says, the abuse of countless civilian prisoners has gone unrecognised. "Some of these women have had children from rape and they are stigmatised in the community," Jolliffe says. They are even taunted as collaborators. The project aims to set the record straight and ensure "that people won't forget what happened, that their suffering would be remembered, and that it wouldn't be in vain".

Jolliffe suggested preserving their experiences on video, but unlike Steven Spielberg's Shoah Foundation's recordings with Holocaust victims, these are not "talking heads". Instead, the approach of the Living Memory Project — set up in 2005 — illustrates the testimony in a style closer to documentary.

Joao Da Costa is filmed outside the former prison, now a four-star hotel, where he was detained in the '70s. He tells of lying on the floor, handcuffed to a woman, both of them beaten and naked.

In compelling footage, he describes how he was burnt on the hands and face with clove cigarettes and how table legs would be placed on his toes, and four Indonesian interrogators would then lean on the chair. He recalls those beaten to death.

In Genoveva da Costa Martins' interview, the pain of loss is still evident as she describes how her husband, nationalist poet Francisco Borja da Costa, was thrown into the sea by the advancing Indonesian army in December 1975.

The project employs professional international freelance film-makers but plans to train locals. Sydney-sider Nicola Daley was chosen because "she had a soft touch and could film women in a sensitive way". An all-female crew is used for filming women survivors of torture, with an assistant on hand to offer counselling if needed.

The five-person project team, some of them ex-prisoners, work from a small overcrowded office in Dili on a shoestring budget. So far they have conducted 50 interviews and assembled an archive of 200 photographs, some taken clandestinely in prison. Backers include the New Zealand Government and the Northern Illinois University. Recently Melbourne's Moreland Community Health Service pledged money for follow-up medical help for ex-prisoners. Jolliffe hopes to raise sufficient funds for a full-time archive where the public can come in at any time to view the films, and where ex-prisoners can meet socially.

The project has also attracted some World Bank funding to stage exhibitions to help bridge the political and ethnic divisions that erupted between the eastern and western regions of East Timor in 2006 amid rising unemployment, and disaffection among the armed forces. Recently, a former prisoner from the western region of East Timor gave a talk to a youth group in East Timor. The World Bank wants similar encounters extended into schools as part of East Timor's healing process.

Meanwhile, the indefatigable Jolliffe has five books behind her and is in the midst of a PhD in creative writing at Flinders University. She is revising her fifth book, Cover-up, about the deaths of the five Australian journalists — the Balibo Five — killed by Indonesian troops two months before the December 1975 invasion. The update will include a report by Deputy NSW Coroner Dorelle Pinch recommending the indictment of General Yunus Yosfiah and Cristoforus da Silva for complicity in the killings.

JOLLIFFE has also enlarged the depiction of journalist Roger East, who died later, in keeping with his central role in a film version of her book, which stars Anthony La Paglia as East. The film script was written by David Williamson and Robert Connolly. It premiers at the Melbourne International Film Festival next July.

Jolliffe is also writing a book, Finding Santana, about her solo journey to the East Timorese mountains in 1994 to interview the East Timorese commander, Konis Santana. She travelled down the Indonesian archipelago by bus and boat to avoid the Indonesian authorities — another front-page story. She has received an Eric Dark Fellowship to stay at the Varuna writers centre, in the Blue Mountains of NSW, to work on it.

Reflecting on the four decades she has devoted to covering East Timor, she says: "I think there was a lot of unfinished business there from my first period as a novelist- journalist. My translator was executed on Dili wharf also (in 1975) and I haven't forgotten that.

"The story of East Timor is one that finds its way into people's psyches and it doesn't go way altogether."

Andra Jackson is a staff writer.