By Lucy Williamson BBC News

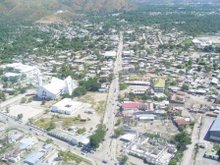

By Lucy Williamson BBC NewsOne day, perhaps, the place where Isabel sits will be a five-star hotel looking out onto the sea near the western corner of Dili's beach road.

But for now, six years after independence from Indonesia, there is just Isabel.

Her flimsy bamboo stall shades her from the sun's glare, her tiny piles of tomatoes and garlic are waiting naked in the afternoon heat for a sale.

Six years of independence, and East Timor's capital city is holding its breath.

Two governments, multinational forces numbering thousands, billions of dollars of international money - and yet people like Isabel are still saying life was better under the Indonesians:

"People could afford to buy things then. Now we just sit here at the stall all day, and perhaps we'll earn a dollar or two."

Resource curse

It is ironic, then, that East Timor has been held up in the past few years as an economic role model - ironic, too, that it has done this by sitting on a large and growing pot of oil savings.

Oil and gas - buried under the Timor Sea - are what give East Timor a future.

They underwrote its independence after the Indonesian army left, taking with it the area's economic lifeline and destroying its sparse infrastructure on their way out.

So far East Timor has built up a fund of about $3bn (£1.63bn). It may not sound like a lot but for a population of less than a million people, in a country where a budget of $300m has proved hard to spend, it is a fortune.

But this economic blessing also comes with a warning. No country like East Timor has ever managed to use a sudden influx of oil money to create a stable and transparent economy.

The developing world is dotted with examples of what economists called the Resource Curse - too much easy money flooding the system, bringing with it inflation, corruption and the death of any private enterprise.

Can East Timor prove that it can, in fact, be done? That taking oil and gas out of the ground can be good for the host country as well as its customers?

Spending spree

Until now, it has largely avoided the usual tripwires.

East Timor's Petroleum Fund was modeled on Norway's - considered to be perhaps the best in the world - and wrapped in safeguards that prevented governments from frittering away the country's future.

But as the account grows, and the frustration of people like Isabel begins to nag at their leaders' consciences, the money is starting to burn a hole in the government's pocket.

This year, for the first time, the government dipped into the fund itself. In addition to withdrawing its usual sustainable amount - basically the interest on the savings - it took a slice of the capital to help fund a 122% increase in the annual budget.

Spending some of East Timor's oil money is not necessarily a bad idea.

Oil and gas revenues currently make up more than 95% of the government's income and there is a pressing need to create a more stable mainstream economy for when those resources run out.

But most of the extra money in this year's budget was to enable the government to subsidise rice and fuel prices - not exactly a contribution to Timor's long-term growth.

And the finance minister herself admits this was more about avoiding potential instability than building a future economy.

Budget race

East Timor's beauty is startling. But you do not have to drive that far south of where Isabel sits at her market stall for the road to peter out into a mountain track.

And try paying for that long and bumpy journey by credit card, or even arranging a taxi after dark, and it is obvious why the five-star hotels are not being built.

East Timor needs roads, electricity and education - and the government knows it.

But red tape and lack of capacity have made it difficult to spend here.

So Prime Minister Xanana Gusmao has recently dismantled some of that bureaucracy, issued tight budget deadlines and started a private ministerial spending race - scored with fruit.

Each ministry now lives in fear of this surreal internal ritual. Spend more than 80% of your budget and you are labelled with a durian fruit - the Timorese government equivalent of a gold star.

No one wants to be a banana - the lowest spenders in the cabinet.

The result, its critics say, is a raft of rushed, badly thought-out projects, many of which seem to have stalled.

The tender processes have often been very short - sometimes a matter of weeks.

Civil society groups - and the opposition - complain they are being kept in the dark, and ministry insiders say corners are being cut, opening the door to corruption.

All of which has landed a few strongly worded letters on the prime minister's desk - some of them from Timor's international partners, worried at the precedents being set.

But this young country still has a shot at getting it right and showing the world the curse can be avoided, and that is really because it has two things going for it.

One is a strong and vocal civil society and a vibrant opposition. The other is its size.

Ironically, East Timor's lack of development and its small, scattered population allow it to look for what some experts term a "21st Century solution" to development - nimble, decentralised programmes that focus on training and mobile services.

So much advice, so much criticism - many ministers sound a little inured to it now.

As the deputy finance minister told me recently: "Sometimes we worry too much. If we worry too much about expenditure, then you also have no result in the end."

True enough. But worry too little, and the result might also be the same.

Story from BBC NEWS:http://news.bbc.co.uk/go/pr/fr/-/1/hi/world/asia-pacific/7629881.stmPublished: 2008/09/24 01:09:02 GMT© BBC MMVIII

Sem comentários:

Enviar um comentário